Many Thanks to Owen Lourie, Project Director, Finding the Maryland 400 at the Maryland State Archives, for writing today’s Post!

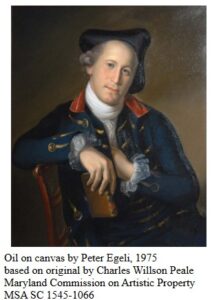

Just over 249 years ago, the United States declared itself to be independent. Eight weeks later, the new nation’s quest for self-rule nearly came to a calamitous end in the fields of Brooklyn, New York. The over-matched Continental Army, led by an untested George Washington, was routed by the British. Only the actions of a small group of soldiers, including the troops now known at the “Maryland 400,” allowed the Americans to survive.

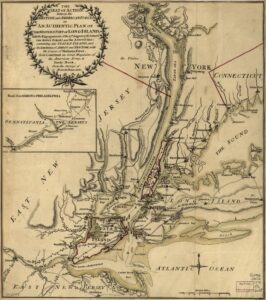

The Battle of Brooklyn, on August 27, 1776, was the first major battle of the Revolutionary War, and the biggest. The Americans had perhaps 20,000 troops defending New York City from the British attack everyone expected. New York was the main target of the British Army, and it had some 31,000 troops at the ready.

As the British began arriving, Washington and his generals were uncertain what their plans were. In mid-August, they landed 15,000 men in the southern end of what is now Brooklyn, but the the Americans were uncertain whether this just a small decoy force. Not until August 26, nearly a week later, did Washington realize it was the main British army and send troops across the East River from Manhattan towards Brooklyn, including some from Maryland.

As the British began arriving, Washington and his generals were uncertain what their plans were. In mid-August, they landed 15,000 men in the southern end of what is now Brooklyn, but the the Americans were uncertain whether this just a small decoy force. Not until August 26, nearly a week later, did Washington realize it was the main British army and send troops across the East River from Manhattan towards Brooklyn, including some from Maryland.

Maryland had sent about 1,000 soldiers to New York that summer, a regiment under Col. William Smallwood and three of the state’s Independent Companies. Only a handful had any military experience, and just two had ever seen combat—back in 1758 during the French and Indian War. Maj. Mordecai Gist led the Maryland troops at the Battle of Brooklyn; Smallwood was required to remain in Manhattan to attend a court martial and could not reach the battlefield in time to join his troops.

The Marylanders were positioned alongside men from Delaware and Pennsylvania on the far right of the American lines. Arriving at their post early in the morning of August 27, they took part in the first fighting of the day. One Maryland soldier wrote:

the British army … advanced within about three hundred yards of us, and began a very heavy fire from their cannon and mortars … now and then taking off a head.

Our men stood it amazingly well … When [the British] perceived we stood their fire so coolly and resolutely, they declined coming any nearer … In this situation we stood from sunrise to twelve o’clock, the enemy firing upon us the chief part of the time.

After successfully weathering this attack, cheers could be heard along the line, and the Americans felt that victory was at hand. Unfortunately, this fighting had only been distraction to give the British time march around the other end of the American lines and encircle them. As a Marylander reported, “the main body of their army, by a route we never dreamed of, had entirely surrounded us, and … scattered all our men, except the Delaware and Maryland battalions.” On the left side of the battlefield, American troops fled in panic, but one the right the Marylanders were able to begin an orderly retreat. They hoped to reach the safety of the fortified American camp at the rear of the battlefield.

As they withdrew, the Maryland soldiers found their way blocked by the marshy and deep Gowanus Creek. About half of them were able to get through, but the rest could not cross and tried to find another route off the battlefield. Instead, they found themselves facing a large number of British soldiers. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, the American general commanding the Marylanders, rallied them, along with some Delaware and Pennsylvania troops, and made a series of charges against the British.

The Americans made a desperate last stand, amid fierce combat. William McMillan, a sergeant from Harford County, recalled that “My captain was killed, first lieutenant was killed, second lieutenant shot through the hand, two sergeants was killed; one in front of me…my bayonet was shot off my gun.” Eventually, they were forced to give way. While some were able to escape, many were killed or, like McMillan, taken prisoner by the British. Observing the fighting below, Washington “wrung his hands and cried out ‘Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose!’”

In all, Maryland lost 256 men killed or captured, about 25 percent of the unit’s strength. However, their stand prevented the British from pursuing the rest of the fleeing American army, buying time for many to escape. Without their actions, the British could well have destroyed the entire Continental Army that day, and crushing the rebellion.

The Battle of Brooklyn was a hard blow to the war for American independence and more blows were to come in the next few months. The Americans were chased out of New York and put on the run through New Jersey. Still, many of the Marylanders reenlisted at the end of 1776 and remained in the army for years to come. About 60 of the Maryland 400 stayed in the army until the war’s final days in 1783, seven long years later. Maryland’s soldiers fought in nearly every major battle of the war, earning a reputation as among the best in the army.

The Battle of Brooklyn was a hard blow to the war for American independence and more blows were to come in the next few months. The Americans were chased out of New York and put on the run through New Jersey. Still, many of the Marylanders reenlisted at the end of 1776 and remained in the army for years to come. About 60 of the Maryland 400 stayed in the army until the war’s final days in 1783, seven long years later. Maryland’s soldiers fought in nearly every major battle of the war, earning a reputation as among the best in the army.

For many years, the Maryland 400 has been remembered as a group, if they were remembered at all. The Maryland State Archives has worked hard to telling the story of each Maryland soldier who fought at the Battle of Brooklyn. We have written biographies of every known soldier, available online. This research is being compiled into a book, which will be published next year for the 250th anniversary of the battle. Learn more about that book and how you can support it.

The Maryland State Archives, led by Archivist Owen Laurie has worked hard to tell the story of each Maryland soldier who fought at the Battle of Brooklyn. Visit the Maryland State Archives website Finding the Maryland 400, where you can learn more about the Battle of Brooklyn, beginning with the British landing, biographies of every known soldier online, or check out their series, The Battle of Brooklyn in Five Objects, and read what the Marylanders themselves remembered in the Oral History of the Battle of Brooklyn.

Want to learn more about the role Maryland’s Patriots played in the Battle for American Independence? Stay tuned for exciting events and activities that will be coming up as we celebrate the 250th in 2026.

Check out the calendar of events at Visit Annapolis and Anne Arundel County for 250 events and activities. You can also pick up your Passport to the 250th at the Visitors Center on West Street.

Want to dig deeper into local stories? Check out the Annapolis 250 Commission’s website or visit the Maryland 250 to learn about State-wide programs.

Other local 250th gems you can visit in the Chesapeake Crossroads include

The Rising Sun Inn, a 1753 house on Generals Highway, is maintained and managed by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The National Cryptological Museum, where you can learn about Revolutionary War spycraft and see Thomas Jefferson’s Cipher Wheel; or

Visit one of the homes of our founding fathers in Annapolis, like the William Paca House & Garden or the Charles Carroll House & Garden.